Ian McKellen’s Hamlet: A Return to Theatre (28th June 2021)

Last Monday night marked a return to the theatre for me, socially distanced and masked it’s true, but I had the privilege of doing it in the company of Sir Ian McKellen and his fellow cast members who have taken up residence in my local theatre for most of the rest of the year.

My last full on theatre experience had been in February 2020 to see Caryl Churchill’s strangely haunting short piece ‘A Number’, and before that we had had a golden few months at the theatre for some sixties kitchen sink nostalgia with ‘A Taste of Honey’ and the musicals ‘Come From Away’ and ‘The Girl From The North Country’, two very different shows, but both innovative and hugely enjoyable. But then the pandemic shutters came down. Stoppard’s ‘Leopoldstat’, postponed and perhaps most painfully the stage version of the excellent Shakespeare comedy ‘Upstart Crow’ was gone just a few days before we were due to be there. So apart from a couple of semi-staged readings locally last October during an abortive attempt to open up again, the in-person theatrical experience was denied to us and we could only do our bit through The Shows Must Go On and the NT Live archive, to try and help out struggling actors and creatives. We were not alone in this of course so last night was quite a night for us and, I’m sure, for all concerned.

And Ian McKellen doing Hamlet. At 82 he is the oldest Hamlet seen in the UK. Something not to be missed, surely. The pre-show publicity has revolved around this being an age blind production, but it’s also gender blind and colour blind. One very notable thing about the production that is worth mentioning up front is the young and diverse cast that Sir Ian and director Sean Mathias have gathered around them. But the big question is, of course, what is an octogenarian Hamlet like? Does it work?

Inevitably perhaps the answer is yes and no, but, for me, the yes outweighs the no. McKellen is one of the best, if not the best, Shakespearean actor of his generation and he is that primarily because of the way he speaks the bard’s verse. He somehow creates a speech pattern that carries with it his years of experience, yet also manages to sound, well, casual. He goes for meaning and understanding rather than strict adherence to the metre and cadence of the prose and poetry, but the effect is much more subtle than that makes it sound. He doesn’t ignore or loose the rhythm of the piece at all, but makes it sound quite natural, which his quite an achievement.

Some lines, some of the most famous lines, are almost thrown away. ‘To Be Or Not to Be’ is delivered into the back of a high chair. Nothing wrong with deciding to make this an intimate speech, just between Hamlet and Horatio, but it is a central speech of the play for a reason, the moment we really begin to close to Hamlet’s thoughts, and it deserves more than it is given here. Having said that it is in keeping with the character of Sir Ian’s Hamlet, portrayed here as a very intimate and casual man. He avoids the Hamlet who wears his innermost life on his sleeve, where his melancholy can veer to the melodramatic, and that is a good thing. Hamlet has fascinated down the centuries precisely because he is a complex human being full of confliction despite his quick mind and clever quips. He is, after all, the spoilt son of a King who expects to be the centre of attention. He can, and does, frequently tell his friends and the other courtiers to leave him alone and they comply.

And it is not only Sir Ian’s ability with language that makes him stand out. He moves around the stage with a fluidity that belies his years and makes younger men, including myself, quite jealous. In this production the representation of Elsinore castle is a suitably dark and brooding affair, it is explicitly for Hamlet a prison, and that is certainly the vibe here. A metal framework of stairs and walkways that clang with every step creates a cold atmosphere. We can feel that there is little love to be had in this dark and misty place and on the occasions that the set is more brightly lit it is with cool and starkly bright strip lighting that does nothing to lift the atmosphere. McKellen’s Hamlet may run up and down the staircases and across the gallery more easily than some of the younger cast manage to manage, but he is a man trapped by the events that precede the action of the play, which he has no control over, until he manages to change that.

I first saw McKellen on stage in 1988, when he was still just under fifty, in Alan Ayckbourn’s ‘Henceforward…’. He still has the same wirery frame and moves around the stage with an ease that I remember he had more than thirty years ago. Apart from a rather truncated fencing bout at the end of the play there is no apparent concession to age. The recognisable traits are there – the hands thrust deep into the pockets, the shoulders that rise and rise until you wonder if they will ever stop – but, wisely, never a hint of Gandalf or Magneto.

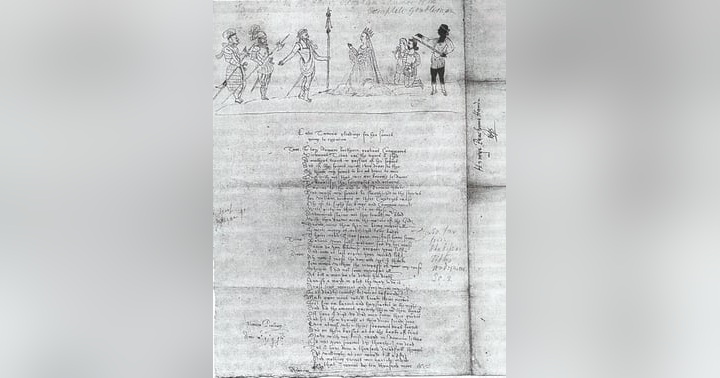

The other time I have seen Sir Ian on stage is much more recent. He played an early night on the tour of his one man show to celebrate his eightieth birthday in this same local theatre – a tour that got extended repeatedly and ended with an originally unplanned west end run at the Harold Pinter Theatre, thanks to its, and his, popularity – and I was lucky enough, well, quick enough on the ticket website, to be there. It was undoubtedly one of the best evenings in the theatre that I have ever experienced. To see an actor of such experience and still at the top of his game was truly an event. He held us captivated with a structured jaunt through his life and career with chucks of Shakespeare, Tolkien, the X-Men and more. At one point he gets out an old schoolbook where he wrote about his hobbies and said ‘Yes, anything to do with the theatre pleases me’. He certainly continued to express that love in spades that evening. You could have heard the proverbial pin drop in the auditorium and given more than a few squeaky seats that we usually have to contend with, that was quite something. There is a filmed version of the show from the West End running on Amazon Prime at the moment and you really should watch it if you have the chance.

I digress, back to Hamlet.

As the play opened, we were of course all watching to see how the age differentials work. Perhaps an odd directorial choice was to have Hamlet deliver the second scene of the play and the lines about ‘too too solid flesh’ while pumping away briefly on a static exercise bike, that smelt a bit of the gentleman protesting too much and jarred, but once we got further into the play the ageing was mostly truly blind as we were swept along by the language. Any oddness in this respect is reduced to moments, like greeting his clearly much much younger student friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, or after the killing of Polonius when he gets up close and personal to his much younger mother.

The ghost played by Francesca Annis is more gender neutral than female and good use is made of some ghostly miking-up. For the other smaller parts, the gender of the casting is truly irrelevant.

There were some other directorial choices that niggled. Jenny Seagrove’s Gertrude spoke with a Danish accent but was the only cast member to do so and I found it rather distracting and Steven Berkoff’s Polonius, while not out of character for the fussy, pedantic old man, was maybe rather too free with pauses, elongations, and repetitions within his lines. I have to admit though he did get the biggest laughs of the evening, so maybe it was just me who took against him.

After the killing of Polonius, behind a tightly packed rail of dresses and coats rather than the traditional arras, we get to the inevitable spiral of the revenge tragedy when we know that the body count is going to be high by the end of the play, and Hamlet is the orchestrator of all this. The arrival of the players is a high point. They are a lively and diverse troupe who made the rather repetitive dumb show and play within the play enjoyable to watch. As the first half closes Hamlet descended through the stage floor, leaving in no doubt as to his ultimate destination.

We, on the other hand only descend to the bar to collect a pre ordered drink and scurry back to our seats, no lingering allowed. While we drink and nibble a crisp or two and discuss the play we are allowed to be relieved of the mask, but they are soon back on. Behind us in the mid-stalls (that’s the Royal Stalls as they are known here, after all the queen is sitting at home just across the street from the theatre) is an empty row and beyond that a family outing of parents and two teenagers. Both youngsters are enthusing about the play and checking plot points with their parents – it’s good to hear lively debate about theatre again.

The second half opens with breezy intent. The first half of the play is inevitably rather long, something that feels more acute here thanks to the slightly lacklustre pace of the first few scenes, but now we are on the roller coaster to the end. Ophelia is a striking presence whenever she is on stage. Her singing is strong and the arrangements of her songs of madness, always a difficult part of Shakespeare in my book, are modern and catch the moment and her declining spirits well. Yorick’s skull is pulled from the earth again and the grave digger reminds us that Hamlet is about thirty, with a wry smile. With Ophelia buried Claudius, played with masterful command by Jonathan Hyde, lays his last plan for Hamlet and we get the final, brief, fencing match. All the following deaths are suitably dramatic, verging on the comic. We end with Horatio wishing the angles to sing Hamlet to his rest, missing the confirmation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s deaths at the hands of the English and the final entrance of Fortinbras as he sweeps in to take control of the situation and the country. That omission gives the ending quite a different tone, confirming the story as rather personal. More a drama of family disfunction than one of the corruptions of the powerful, by removing the political overtones that a different production would pick out.

An inevitable and deserved standing ovation for Sir Ian and the cast.

The theatre capacity is usually eight hundred and fifty people, but of course until mid-July the restrictions mean the capacity is much reduced – at least halved I would guess, but as we spilled out of the building, trying to keep some distance from each other, the overwhelming feelings were of gratitude that we had been part of that evening and hope that this was indeed the start of a true return to the theatre and that this latest round of plague closure was indeed coming to an end. It is a thought-provoking production, but not for the reasons one might expect and I, for one, think that Sir Ian has done his reputation no harm at all and say a hearty ‘bravo’ to him to taking this on. Roll on September when we will be treated to the same company playing The Cherry Orchard where, I sincerely hope, we will be crammed into the theatre, one of eight hundred and fifty, just like we used to be. Sir Ian will be playing the age-appropriate family servant. Something to look forward to.

Welcome back theatre. It’s been too long.